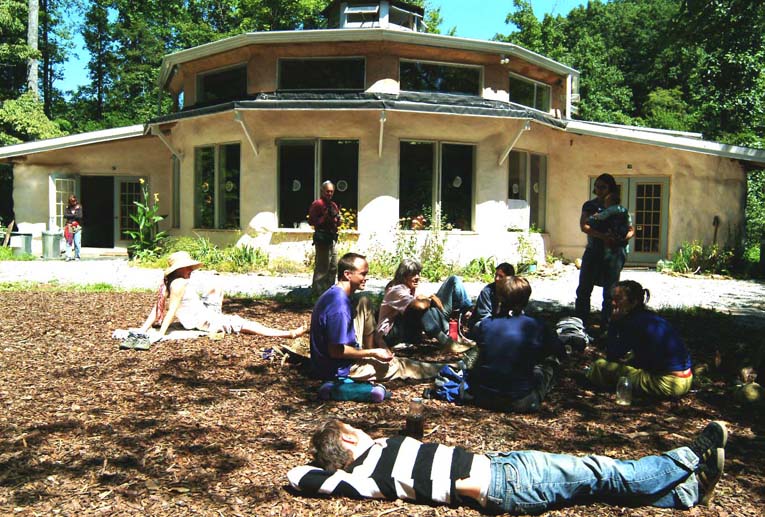

Two North American ecovillages—Earthaven in North Carolina and Dancing Rabbit in Missouri (www.earthaven.org; www.dancingrabbit.org)—have recently implemented new governance and decision-making methods. As an admitted community governance nerd, I’m fascinated by how communities govern themselves and make decisions, and how they innovate new methods when things don’t seem to be working well. I’d like to tell you what these two ecovillages did, because they exemplify a growing trend among communities internationally to innovate new governance methods or try alternative ones.

Governance and decision-making are actually two different things. Governance is what the group makes decisions about, how they organize their different decision-making bodies (i.e., whole-group meetings and committees), and the responsibilities and decision-making authorities they assign to each. Decision-making is how they make these decisions, and is part of governance. Consensus, majority-rule voting, and supermajority voting, for example, are decision-making methods. Sociocracy and Holacracy are whole governance structures that include decision-making methods.

Decision-Making at Earthaven

In June 2014, Earthaven Ecovillage, where I live, changed its decision-making process radically. Many community members were so fed up with too-frequent blocking and “blocking energy” (threatening to block) that we threw out blocking altogether. We kept the consensus process of discussing and modifying proposals—but replaced approving, standing aside, or blocking with a way to acknowledge those who don’t support the proposal, followed by a supermajority vote.

Here’s how our new method works.

After much discussion and likely modifications of a proposal over at least two whole-community business meetings, when it’s time to decide, the facilitator asks if anyone remains unfavorable to the proposal. If no one says they feel unfavorable to it, it passes right then and there.

However, if one or more members present don’t support the proposal, each is asked, one at a time, why they believe the proposal either violates Earthaven’s mission and purpose, or why passing it would be more harmful or dangerous for the community than choosing an alternative proposal or doing nothing.

Their comments are recorded in the minutes. This is followed by a minute of silence. The facilitator asks the question again, so anyone else who may now realize they don’t support the proposal for either of these reasons can say why. Their comments are recorded in the minutes. This minute of silence and the request for any more non-support comments is repeated a third time.

This part of our new process is not about making a decision. It’s about offering those who don’t support the proposal three more opportunities to influence others about the proposal before the vote is taken, and to give them a chance to be heard and acknowledged.

The facilitator then calls for a vote and counts the numbers of Yeses and Nos. There are three possible outcomes:

(1) If 85 percent or more say Yes to the proposal, it passes. That’s it—bang, done—passed.

(2) If less than 50 percent say Yes, the proposal does not pass. (Though its advocates can rewrite the proposal and try again in the future if they like.)

(3) But if the number of Yeses falls somewhere between 50 percent and 85 percent, the proposal does not pass—as there’s not enough support for it—but it’s not laid aside either. Rather, a few of the members who said No and a few who said Yes are required to participate in a series of solution-oriented meetings to create a new proposal to address the same issues. These meetings are arranged by the community’s four officers, and a facilitator is appointed.

If a new proposal is created in the series of meetings it is presented at the next business meeting and we start anew.

But if the advocates for and those against the first proposal do not create a new proposal, the first proposal comes back to the next business meeting for another vote. This time it passes if 66 percent or more say Yes.

What Motivated Earthaven’s Changes

The purpose of this proposal, according to its creators, was “to clarify and simplify our governance process so that it is more sustainable, fair, and effective.” They wanted to give non-supporters of a proposal a chance to co-create a new one they could live with, while preventing what they described as “the gridlock and entrenched ‘stopping’ positions sometimes expressed by a few members.”

In my opinion this new “85 percent passes” method is the inevitable outcome of the “fed up” factor at Earthaven—a factor which motivated two previous changes in our community decision-making processes, and without which this proposal would probably have gone nowhere.

For years Earthaven used what I call “consensus-with-unanimity”—meaning it takes 100 percent of people in a meeting (except stand-asides) to pass a proposal, and there is no recourse if someone blocks. In other words, in consensus-with-unanimity, anyone can block a proposal for any reason and no one can do anything about it.

At the same time we had several members who consistently blocked proposals most others wanted. One member’s “blocking energy” in response to specific proposals in meetings (and even to various ideas mentioned in informal conversations) had the effect of preventing many people from creating a proposal—or even talking with others about a new idea—they knew this member would block. Thus, even though they didn’t intend it, a few members held a power-over position in the community because they could, and did, stop some things almost everyone else wanted. Sometimes this is called “tyranny of the minority.”

Our many attempts to engage with these members—whole-group “Heartshares,” mediations, pleas by individuals or small groups to please stop blocking or expressing “blocking energy”/threatening to block, didn’t change anything—the blocking and threats to block continued. Our consistent blockers saw themselves as protecting the community and protecting the Earth from our community members. And while most of us know thatpeople who block frequently may not be living in the right community (as renowned consensus trainer Caroline Estes points out), no one could bring themselves to suggest that these folks leave Earthaven and find another community more aligned with their values.

The result was discouragement, demoralization, and dwindling meeting attendance. We especially missed the participation of our young people. When younger members first joined Earthaven they’d be eager to participate in meetings, offering high energy and new ideas. But soon they’d become so turned off that they stopped attending meetings. And so in the last few years Earthaven became a de facto geriocracy—with most decisions made by folks over 50.

Earthaven’s First Big Decision-Making Change

In my opinion, our new “85 percent passes” method passed only because of the two previous changes we’d made in our decision-making process.

The first change, originating in 2007 and proposed in 2012, was to create criteria for a legitimate block and a way to test it. We said that for a block to be valid at least 85 percent or more members present should believe the proposal violated Earthaven’s mission and purpose or be harmful or dangerous to the community if passed. However, if less than 85 percent believed this, the block would be declared invalid and the proposal would pass.

If we had one to three valid blocks, the next step would be to convene a series of solution-oriented meetings between proposal advocates and those who blocked, in order to create a new proposal. But if they didn’t produce a new proposal, the original proposal would come back for a decision rule of consensus-minus-one. This meant that if only two people blocked the returned proposal, it would not pass.

Consensus-minus-one was not what most community members wanted—the original proposal had a 75 percent supermajority fallback, not consensus-minus-one. However, our most frequent blocker, who had blocked 10 times over a five-year period, said she would not approve the proposal unless we replace the 75 percent fallback with consensus-minus-one. So the community agreed. Why? It had taken the ad hoc governance committee two years to even come up with this proposal, as it required shifting out of the paradigm that 100 percent consensus is beneficial, and it took awhile for the committee to understand this. And, fearing the effects and repercussions of shock and outrage by the consistent blockers, the ad hoc governance committee disbanded without even making this proposal.But one of the committee members, dismayed by the continued difficulty in meetings, proposed it himself two years later.Then came another year of high emotions in meetings when discussing it, and many proposal revisions, before the community approved even this truncated version.

The original proposal advocates and most community members figured that passing the consensus-minus-one version was better than nothing.

(Over the next year Earthaven used this new method twice, each time declaring a block invalid because only a few members present thought the block was valid. However, with no validated blocks during this period we never had the opportunity to convene any solution-oriented meetings either.)

Earthaven’s Second Big Decision-Making Change

A year and a half later, in January 2014, we passed a second change—to keep this consensus method, with criteria for a valid block, but replace the consensus-minus-one fallback with a supermajority vote of 61.8 percent (Phi in mathematics). This fallback vote would be used rarely, only after a series of solution-oriented meetings in which proposal advocates and blockers failed to create a new proposal.

I believe the exceptionally low number of 61.8 percent for a supermajority vote—the lowest I’ve ever seen in the communities movement—was motivated by backlash against our history of blocking.

(And as noted above, our third and latest decision-making change in June 2014 raised the voting fallback number from 61.8 percent to 66 percent if after solution-oriented meetings no new proposal is created.)

In my opinion, our first two first decision-making changes were like small levers, incrementally prying our community loose from feeling discouraged and intimidated by our consistent blockers.

Our first decision-making change in 2012, while arduous and hard won, allowed us to even imagine we could pass proposals most of us wanted, and gave us the ability, in literal decision-making power, to do so. And our second decision-making change in 2014 gave us even more power to do this.

I imagine Communities readers who believe 100 percent consensus creates (or should create) more harmony and trust in a group, and/or who have experienced 100 percent consensus working well, may be appalled at our choice to replace calling for consensus with voting. Yet, as we’ve incrementally changed our method over the last two years, we have reversed the percentages of people who feel hopeful and those who feel discouraged and demoralized. For years now, many of us felt disheartened about our decision-making process, while a few believed it was fine. But after this series of changes, this has reversed: just a few members feel awful—certain Earthaven has gone to hell in a handbasket—but many more are beginning to feel hopeful again.

Why Dancing Rabbit Changed its Governance

In the summer of 2013 Dancing Rabbit Ecovillage in Missouri made their own dramatic change in governance—shifting from whole-community business meetings to a representational system (using consensus) with seven elected members. Their reasons for change had nothing to do with using consensus, which worked fine for them.

Dancing Rabbit began thinking about change in 2009, when they realized how their growth in membership had altered their social structure. In earlier years everyone ate together in the same place at the same time, giving them frequent daily opportunities to connect and talk informally about community issues. But as their members increased and they created several kitchens and eating co-ops, their social scene offered far less connection. They were no longer the same kind of cohesive group that could informally discuss community issues on a daily basis. As a result, their governance system didn’t work as well: meeting attendance was down, people formerly involved in governance were getting burned out, the smaller number of folks who still attended meetings had more say than anyone else, and some decisions took longer than they once would have. This was partly due to the community’s increasing size, and partly due to simply not knowing each other as well as they once had.

The Village Council System

Dancing Rabbit’s new Village Council consists of seven community members elected by the members for staggered terms of two years each. These seven representatives now make the decisions formerly made by whole-community meetings:

● Creating and dissolving committees and approving committee members

● Approving and modifying job descriptions for specific community roles and paid staff

● Approving the group’s annual goals and priorities; approving the budgets for Dancing Rabbit’s two legal entities (an educational nonprofit, and a land trust through which daily community life is organized)

● Making committee-level decisions when requested by a committee

● Making membership decisions, including revoking membership, when these decisions can’t be resolved by the regular membership process

● Revising group process methods; clarifying or weighing values on various topics, including covenant changes

● And any other responsibilities not already covered by a committee that Council members or Dancing Rabbit’s Agenda Planners think are worthy of Village Council attention.

“It’s refreshing to work with a smaller group that’s been picked to be good decision-makers, and to be able to move forward despite concerns from people not on the Village Council,” says Dancing Rabbit cofounder Tony Sirna. “The community seems to be adapting well to this process, with people accepting that they won’t always get what they want (just like in full-group consensus but without as much time spent on the process).”

Empowering Committees with “Power Levels”

Dancing Rabbit has many committees, all of which essentially report to the Village Council. A committee called the Oversight Team provides the executive function of staffing committees and making sure they do their jobs. Committees have the power to propose policies in their area of responsibility, and implement policies.

The power to make decisions, however, depends on which of four “power levels” a committee has. The “propose” level is the power to make a proposal, and every committee and individual member or resident has “propose” power.

Some committees also have “review” power, which means they can send a proposal to the whole community by email. This starts a two-week comment period, during which concerns can be expressed, changes can be made, and everyone has a chance to suggest changes to or buy in to the decision. At the end of two weeks, if there are no unresolved concerns, the committee’s proposal automatically passes.

Other committees have “recall” power. This is almost identical to “review” power, but the committee doesn’t need to wait until the end of the two-week period and can implement a proposal immediately. However, if concerns are expressed in the two-week period, the committee may need to modify the proposal.

“Final decision” power means making and approving a proposal immediately, without a review period. The Village Council has this power for most decisions, as do meetings of the whole community, if such a meeting were to be called. At first it was rare for a committee to have “final decision” power (the Contagious Disease Response Team uses this power to declare a quarantine, for example), but the power to make decisions has become more common as the community delegates more authority to committees.

A committee can also have multiple power levels for different types of decisions. For example, a committee could use “review” power to propose a budget, and after receiving approval could use “final decision” power to approve minor changes in it.

After creating the Village Council, Dancing Rabbit added two more power levels. Committees or individual members may be given a “Village Council review” level, in which they send a proposal to the Village Council and the whole community. Everyone is free to comment on it during a two-week period, but the final decision rests with the Village Council.

Similarly, in the “Village Council recall” level a proposal is given a two-week comment period but the Village Council can implement it immediately.

Selecting Village Council Members

While the process for selecting Village Council members doesn’t involve consensus per se, it seems infused with the spirit of Dancing Rabbit’s consensus culture.

Here’s how it works. The names of every community member and resident (who has lived there at least three months) are listed alphabetically on a ballot form given to everyone. (Exceptions are the community’s Selection Shepherds, who serve a one-year term to manage Village Council elections.) Each person fills out the ballot form, evaluating each person in terms of how they might serve as a Village Council member.

Evaluation choices are:

+2 “I think this person would be good in this role.”

+1 “I feel OK about this person in this role.”

0 “I have no opinion about this person re this role.”

-1 “I don’t think this person would be good in this role.”

The Selection Shepherds tally the points and the 20 people with the highest number of points are eligible to be nominated for the Village Council on a seven-member slate. A slate includes returning Council Members and the three or four new ones.

A whole-community meeting is held in which people present and discuss various possible slates of seven eligible members each, and choose from one to five of what seem like the best slates of nominees. The nominees are considered according to the following criteria: the person knows how to consider what’s best for the community as a whole; understands the community’s mission, sustainability guidelines, and ecological covenants; has the time; is willing to participate in conflict resolution if needed; is a member in good standing (paid up on dues and fees and up-to-date with labor requirements); and preferably has the use of a computer and has had consensus training. And at least some nominees for a slate need good verbal, written, and/or financial skills.

In this meeting, ideas about people for these slates are discussed, combined, and whittled down, and the group ends up with up to five different slates, chosen either by consensus or, if agreement can’t be reached for one slate by consensus, by a dot-voting system.

At that point all members vote on the slate of nominees they want, using a computer-based instant runoff system. The slate with the most number of votes becomes the new Village Council.

Consensus at Dancing Rabbit

Village Council members use consensus to make decisions, as do the smaller committees. As in many other intentional communities, the basis of Dancing Rabbit’s consensus culture is the belief that people should always have a chance to share their opinions and concerns, and decisions aren’t made until everyone who speaks up is taken into account. And…they expect community members to take responsibility for how their own consciousness may affect community decision-making. “Consensus requires us to make decisions that are best for the group as a whole, and being able to distinguish between our personal wants, fears, and agendas and the group‘s good—which is essential to making a positive contribution,” they write in their Process Manual.

As advised by most consensus trainers, Dancing Rabbit members believe that blocking should be a rare occurrence if the community is functioning well and its members are in alignment with its values and process. Thus they have a clear blocking policy and a way to test for the legitimacy of a block. For example, someone objecting to a proposal is expected to stand aside, not block, if their objection is based on personal values rather than on shared common values. And conversely, it is expected any block will be based on one or more shared community values, or by the belief that passing the proposal would damage the community.

Dancing Rabbit used consensus in its whole-community meetings, and a block was considered valid if it was based in one of the stated community values and at least three other members could understand (but did not necessarily agree with) why the person felt this way. If someone were to block frequently, the Conflict Resolution Team would help the person and the whole group talk about it, with the possibility of setting up an ad hoc committee to work through the issues.

Now, in their seven-member Village Council, a block is considered valid if one other Village Council member can understand (but not necessarily agree with) the blocking person’s position in relation to shared community values. It is also expected that any Village Council member who blocks has made a reasonable effort to participate in the group’s discussion. It is also expected that other Council Members have been reasonable too, giving the person adequate time to consider and comment on the proposal. (Village Council decisions can also be recalled by 25 percent of Dancing Rabbit members.)

I’m impressed by how Dancing Rabbit innovated a whole new governance method in response to the social effects of their increased membership. This took foresight and pluck! While I’ve called the new methods of Earthaven and Dancing Rabbit “radical,” Tony Sirna points out that their new method isn’t actually radical (except for using consensus instead of majority-rule voting) because they intend to grow to the size of a town of 500 to 1000, and small towns typically use representative governance with elected Councils.

I hope you’ve found these innovative new methods stimulating food for thought. Working to shift a whole community’s paradigm about governance and decision-making takes courage, energy, and time. And…it can be really worth it!

This article was adapted from a piece that first appeared in the online GEN Newsletter: gen.ecovillage.org/en/news.

Diana Leafe Christian, author of Creating a Life Together and Finding Community, speaks at conferences, offers consultations, and leads workshops internationally. She specializes in teaching Sociocracy to communities, and has taught Sociocracy in North America, Europe, and Latin America. See www.DianaLeafeChristian.org.

Saint Michaels Eco Village

It is always nice to read these type of articles.