It’s easier to recognize an intentional community when it’s rural. There’s simply less distraction and less interaction with the surrounding population. This has its pros and cons. The escapism and isolationism that was prevalent in the 60’s and 70’s came at a cost to the movement, there are undoubtedly levels of experimentation that being rural makes easier.

And yet, we have these cities. Lots of them. And lots of people live in them. More than half the world’s population.

Are cities sustainable? I don’t think we know the answer. But I don’t think the ecosystem could handle it if everyone who lives in cities moved out in the country tomorrow. Given the current global population, some amount of density seems inevitable. Regardless, we have all these people who live in these cities, and transforming them is going to take a while.

We have to start somewhere. We need more models of urban community.

The Los Angeles Eco-Village has been on my list to visit since the early 2000’s. It’s one of the more well-known communities, especially among urban communities, and especially among ecovillages. It’s original conception dates back to early 1980’s, before the term ecovillage ws even coined, and was reconceptualized following the Rodney King uprising in LA in 1992. The first apartment building was bought in several years later.

The original concept, which had city support, at least in theory, was to make use of an undeveloped 11 acre site in the city that had been a landfill. But after the 1992 uprising, the group made the decision to just do it in the neighborhood where founder Lois Arkin had already been living for 13 years. What followed was a solid effort in neighborhood organizing and community building simply as residents of the existing neighborhood, particularly focused on engaging with kids, until they were ready to start purchasing property.

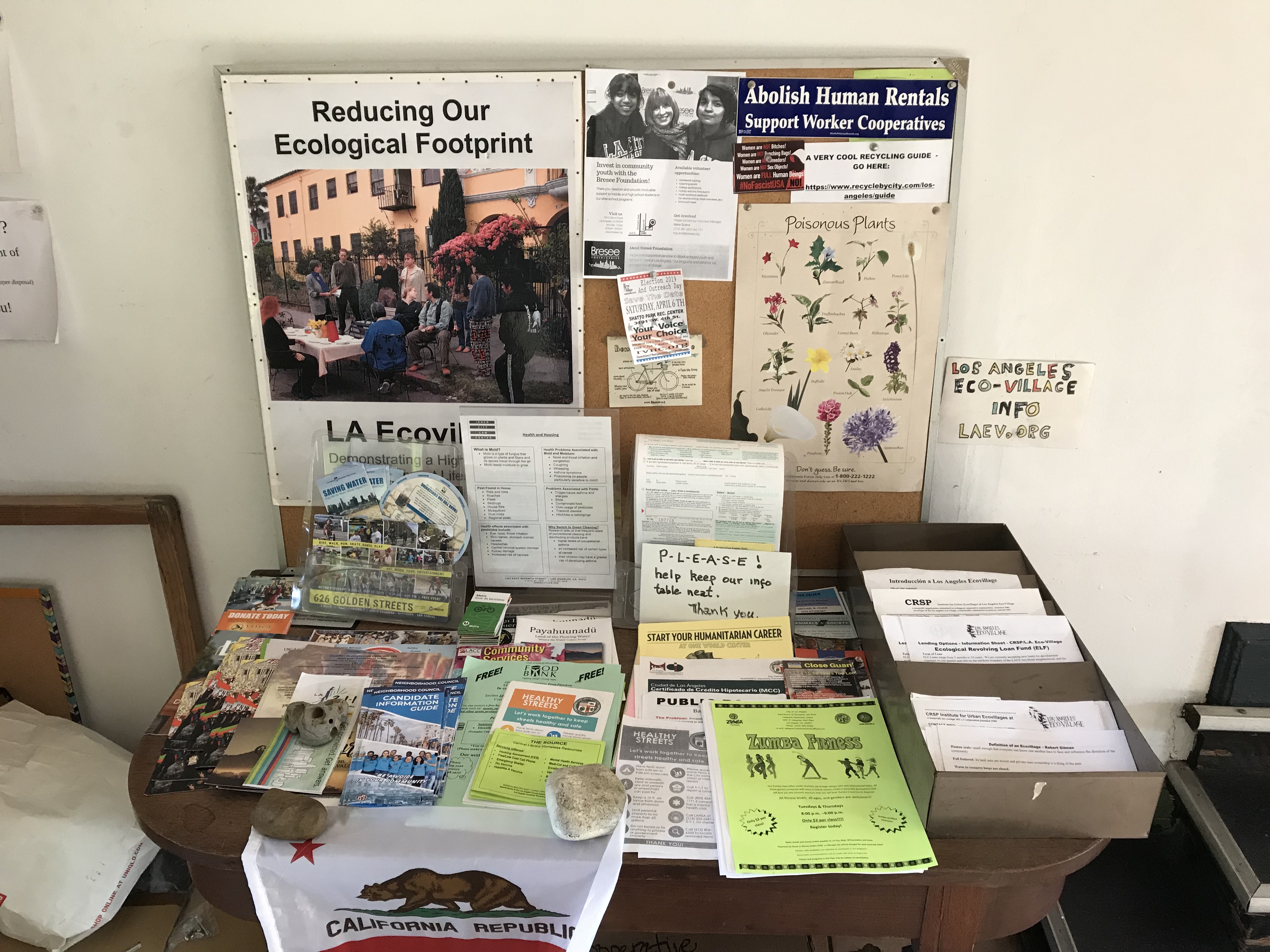

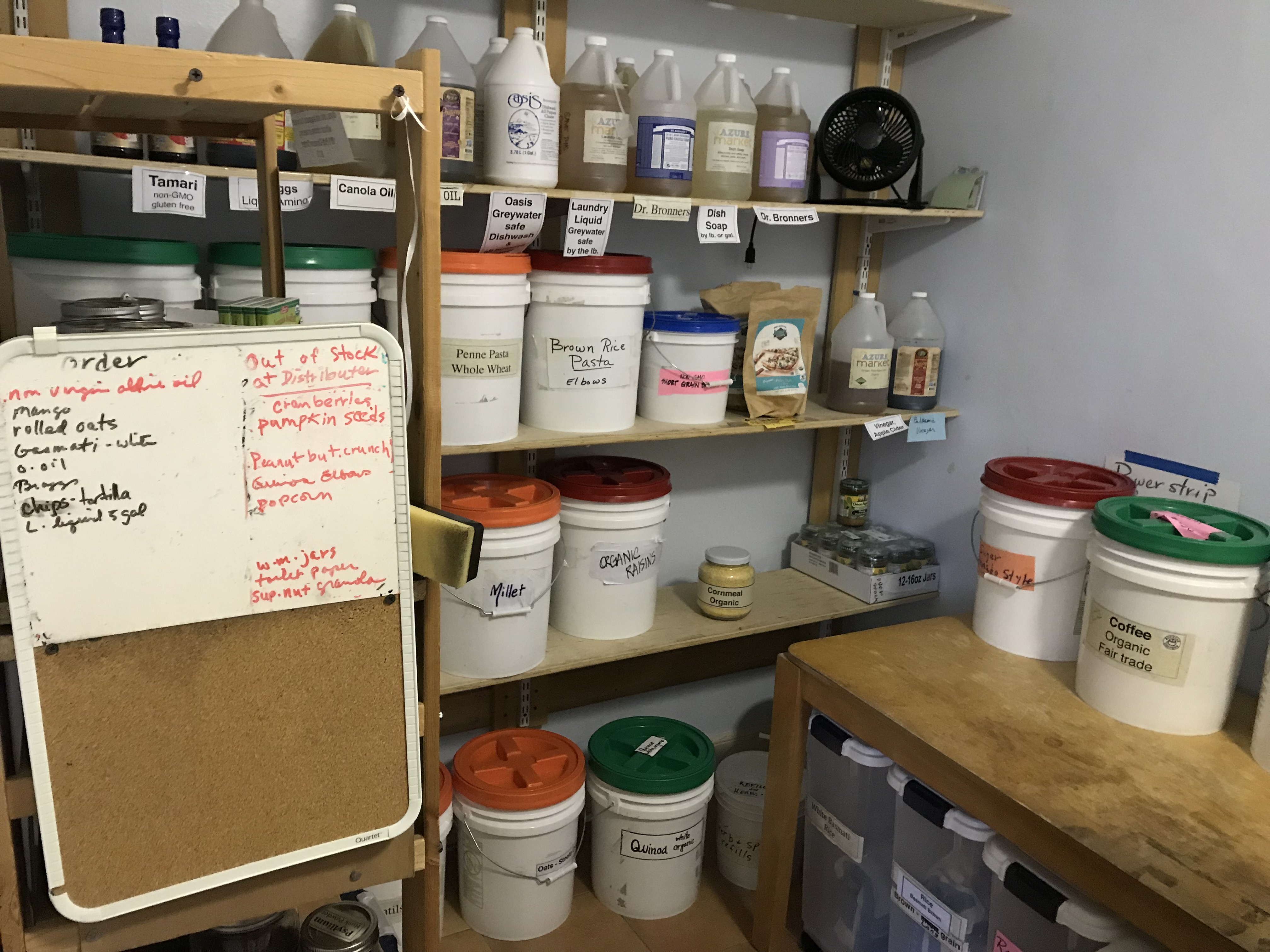

Los Angeles Eco-Village (LAEV) is actually a placeholder name. There’s no legal entity with that name. The two apartment buildings are organized as the Urban Soil/Tierra Urbana Limited Equity Housing Co-op (LEHC). At some point the Beverly-Vermont Community Land Trust was formed to hold title to the land under the Housing Co-op. The CLT also owns a fourplex and old garage, and the garage has been leased to one of the ecovillagers for a bike shop. And then there’s the Cooperative Resources & Services Project (CRSP), an educational non-profit, which acted as the original developer for the ecovillage and operates a revolving loan fund. More recently CRSP bought the hold auto garage adjacent to the first apartment building, which it’s been remediating for lead, asbestos, and hydrocarbons, and plans to develop into a small co-operative business hub. A small food co-op of about 60 members called the Food Lobby also operates out of the ecovillage, including both residents and non-residents. Also, on the intersection with the ecovillage is a learning garden that’s owned by the school district but managed by the ecovillage.

In other words, there’s a lot going within several different organizational structures, with lots of overlap of who’s involved, and everyone identifies it all together as LAEV.

LAEV has definitely put some best-practices to good use.

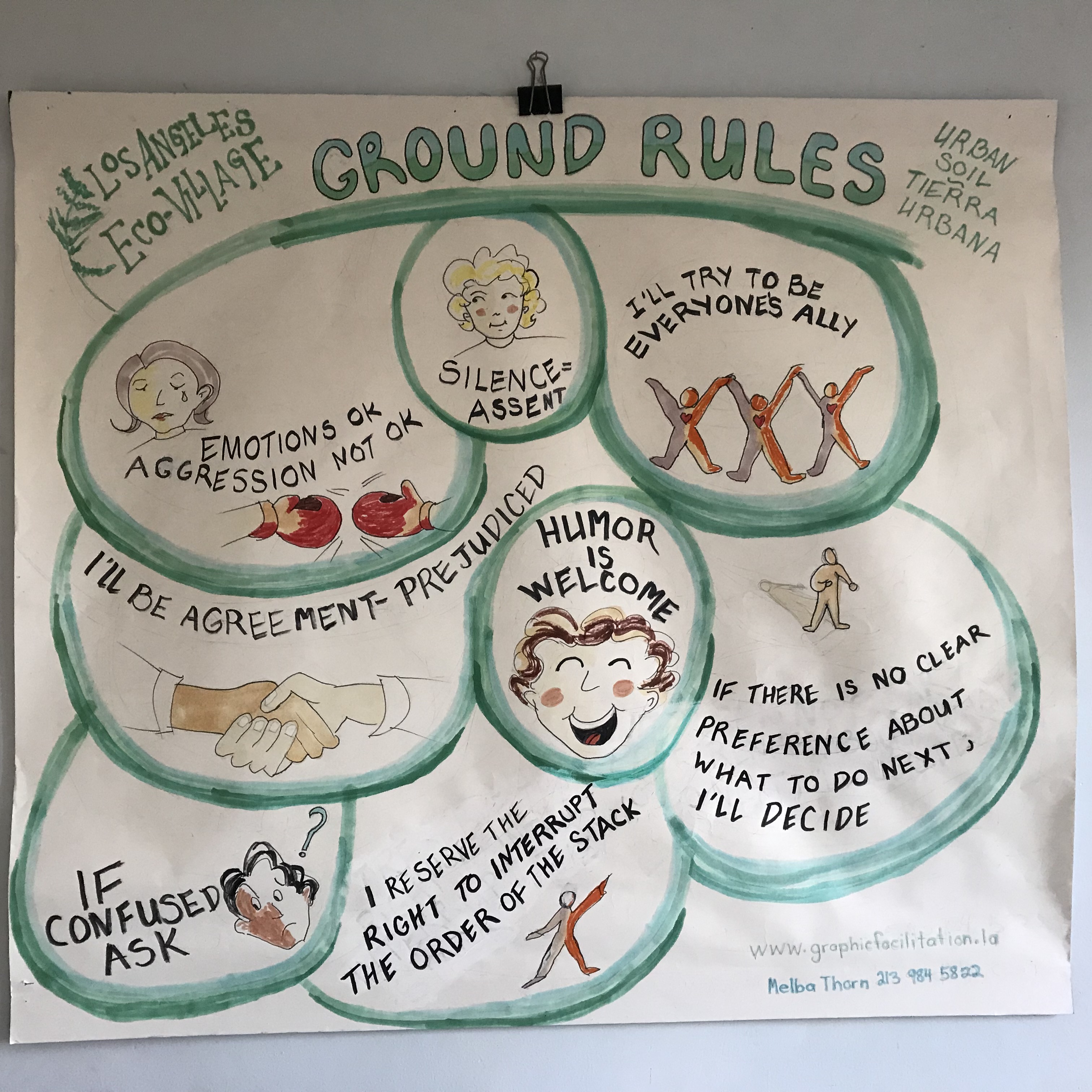

They created a sufficiently but not overly complicated legal structure. At the same time, they were very intentional about building the culture of the group so that they values underlying the culture and legal structure were in synch, and from the beginning worked to make sure that all of this would be solid enough to outlive the founders. Succession planning is a topic more communities need to look at.

They’ve developed or supported economic opportunities, which, in additional to the benefits to members, helps people engage in more in the life of the community. Having a food co-op that’s available to non-residents helps grow their extended community, the strength of which is good indicator of the health of a community.

They’ve supported activism in the city, particularly helping foster to bike culture and community bike resources in Los Angeles.

They started off by making sure they were integrated into the neighborhood. I think this is so key. At some point we have to figure out how to create intentional communities amongst people where they are. Everywhere people live, urban or rural, you can identify clusters of people in proximity you could call a community. Let’s call them incidental communities. How do we turn these incidental communities into intentional communities? This is part of the question LAEV.

But while their efforts to integrate in the neighborhood were successful, they ended up being limited. As the community bought housing and started developing they turned inward more, and more than 20 decades later, most people in the neighborhood have moved, as have people in the ecovillage, and they’re seeing how there’s a need to return to that neighborhood engagement. While I was there they hosted a public form for candidates running for Neighborhood Council, and a couple ecovillagers are running for council (ecovillagers have sat on the Neighborhood Council before as well).

They also seem like a mature community that has its version of a classic issue: Getting people to engage and participate. It’s pretty easy for groups that are bigger than, say, 20 to get settle in and start attracting people who like the community but kinda just want to do their own thing. I don’t want to say this inevitable, but it’s incredibly common, and if the cultural gravity trends in that direction can definitely create problems. It didn’t seem that bad at LAEV. Again, there’s a lot going on with the at least 5 definable organizations operating there and a rich social life, but it was interesting to see a familiar pattern in another setting.

At the same time, LAEV hasn’t just settled in. They’re continuing to grow and develop, and seem to be at a point where they have the financial and legal resources, and the people, to grow pretty fast if they want to, or at least start putting themselves out more. Lois said they’ve been hesitant up till now of being too public because they didn’t feel like they were ready. But that seems to be shifting now that they’ve become something you can look at and really see how the vision for sustainable urban community can be put into practice.